(Published in The Nation, 21 May 2014)

Shawn Kelly

SPECIAL TO THE NATION

Not many saw it coming. The strongest ever earthquake with an epicentre

in Thailand caught the country off guard as it struck the North with

deadly intensity. Killing one and injuring twenty-three, the powerful

6.3-magnitude shudder that shook Chiang Rai province on May 5 cleaved

gaping fissures in highways and damaged thousands of homes, Buddhist

temples, ancient heritage sites, schools, hospitals and

utilities.

The quake frightened an unsuspecting populace who scurried for safety

in the early evening twilight - and even rattled the nerves of people

inside swaying skyscrapers in distant Bangkok. Still, it was not the

first time the capital's terra firma has moved.

When the deadly Great Sichuan Earthquake killed 70,000 Chinese in

2008, its powerful shockwaves rippled south to Thailand 2,000

kilometres away. And when a magnitude-6.8 tremor killed 13 people in

the Mandalay region of Myanmar on November 11, 2012, it too was felt

over 700km away in the nation's metropolis.

To be sure, the country is not as exposed to earthquakes as say Japan,

Indonesia or New Zealand, and it does not sit directly atop the fault

lines of the Pacific Ring of Fire, where 90 per cent of the world's

earthquakes occur. However, as the Chiang Rai upheaval proved, the

Kingdom is far from immune to their terror.

Witness the immense loss of life and catastrophic damage from the

tsunami unleashed by the giant quake of December 2004 off the coast of

Sumatra, and one can see just how dangerous the country's neighbourhood

can be. Add to the volatile mix the 14 known fault lines that

criss-cross the nation's North and Western border frontier - including

the newly discovered 30km Ongkarak fault passing through Nakhon Nayok,

Saraburi and Lop Buri provinces - and Greater Bangkok's 10 million-plus

residents may be vulnerable to seismic hazards.

In fact, distant large earthquakes occurring over the horizon are a

genuine threat to Bangkok. That's the sobering warning Dr Pennung

Warnitchai, a noted seismological expert at the Asian Institute of

Technology (AIT), has been sounding for some time. The structural

engineer said that when an extremely large quake eventually rumbles

across the region many structures in the capital will suffer serious

damage and some with structural weaknesses will collapse.

Now, researchers from AIT, Thammasat and Mahidol universities have the

smoking gun to back up that claim. As part of a one-year research

project completed for the Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Department

of the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA), three teams of

experts led by Pennung produced a statistical model that identifies the

impact to the city's skyscrapers, including 1,434 buildings taller than

12 storeys and 645 above 20 floors.

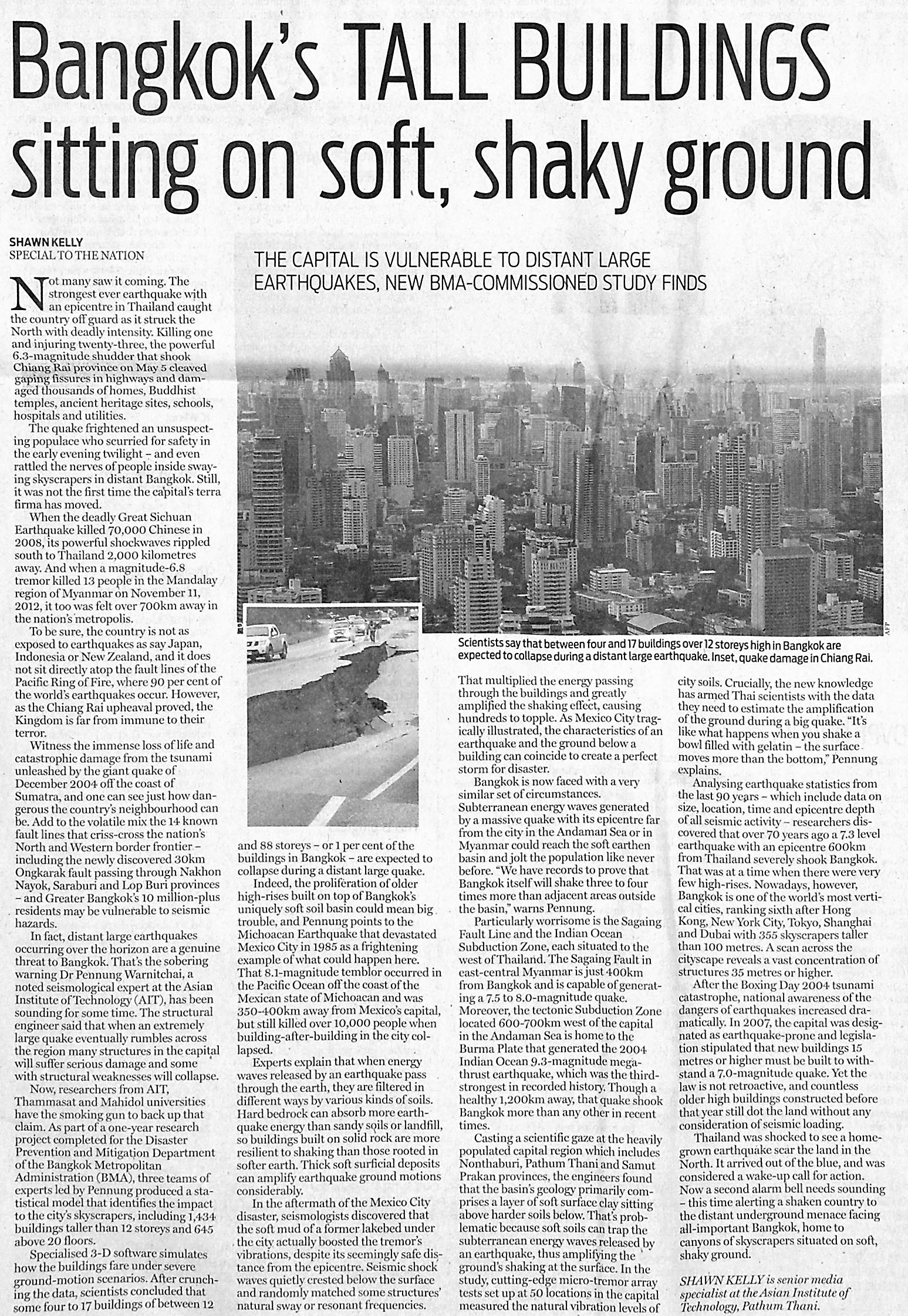

Specialised 3-D software simulates how the buildings fare under severe

ground-motion scenarios. After crunching the data, scientists concluded

that some four to 17 buildings of between 12 and 88 storeys - or 1 per

cent of the buildings in Bangkok - are expected to collapse during a

distant large quake.

Indeed, the proliferation of older high-rises built on top of

Bangkok's uniquely soft soil basin could mean big trouble, and Pennung

points to the Michoacan Earthquake that devastated Mexico City in 1985

as a frightening example of what could happen here. That 8.1-magnitude

temblor occurred in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of the Mexican

state of Michoacan and was 350-400km away from Mexico's capital, but

still killed over 10,000 people when building-after-building in the

city collapsed.

Experts explain that when energy waves released by an earthquake pass

through the earth, they are filtered in different ways by various kinds

of soils. Hard bedrock can absorb more earthquake energy than sandy

soils or landfill, so buildings built on solid rock are more resilient

to shaking than those rooted in softer earth. Thick soft surficial

deposits can amplify earthquake ground motions considerably.

In the aftermath of the Mexico City disaster, seismologists discovered

that the soft mud of a former lakebed under the city actually boosted

the tremor's vibrations, despite its seemingly safe distance from the

epicentre. Seismic shock waves quietly crested below the surface and

randomly matched some structures' natural sway or resonant frequencies.

That multiplied the energy passing through the buildings and greatly

amplified the shaking effect, causing hundreds to topple. As Mexico

City tragically illustrated, the characteristics of an earthquake and

the ground below a building can coincide to create a perfect storm for

disaster.

Bangkok is now faced with a very similar set of circumstances.

Subterranean energy waves generated by a massive quake with its

epicentre far from the city in the Andaman Sea or in Myanmar could

reach the soft earthen basin and jolt the population like never before.

"We have records to prove that Bangkok itself will shake three to four

times more than adjacent areas outside the basin," warns Pennung.

Particularly worrisome is the Sagaing Fault Line and the Indian Ocean

Subduction Zone, each situated to the west of Thailand. The Sagaing

Fault in east-central Myanmar is just 400km from Bangkok and is capable

of generating a 7.5 to 8.0-magnitude quake. Moreover, the tectonic

Subduction Zone located 600-700km west of the capital in the Andaman

Sea is home to the Burma Plate that generated the 2004 Indian Ocean

9.3-magnitude mega-thrust earthquake, which was the third-strongest in

recorded history. Though a healthy 1,200km away, that quake shook

Bangkok more than any other in recent times.

Casting a scientific gaze at the heavily populated capital region

which includes Nonthaburi, Pathum Thani and Samut Prakan provinces, the

engineers found that the basin's geology primarily comprises a layer of

soft surface clay sitting above harder soils below. That's problematic

because soft soils can trap the subterranean energy waves released by

an earthquake, thus amplifying the ground's shaking at the surface. In

the study, cutting-edge micro-tremor array tests set up at 50 locations

in the capital measured the natural vibration levels of city soils.

Crucially, the new knowledge has armed Thai scientists with the data

they need to estimate the amplification of the ground during a big

quake. "It's like what happens when you shake a bowl filled with

gelatin - the surface moves more than the bottom," Pennung

explains.

Analysing earthquake statistics from the last 90 years - which include

data on size, location, time and epicentre depth of all seismic

activity - researchers discovered that over 70 years ago a 7.3 level

earthquake with an epicentre 600km from Thailand severely shook

Bangkok. That was at a time when there were very few high-rises.

Nowadays, however, Bangkok is one of the world's most vertical cities,

ranking sixth after Hong Kong, New York City, Tokyo, Shanghai and Dubai

with 355 skyscrapers taller than 100 metres. A scan across the

cityscape reveals a vast concentration of structures 35 metres or

higher.

After the Boxing Day 2004 tsunami catastrophe, national awareness of

the dangers of earthquakes increased dramatically. In 2007, the capital

was designated as earthquake-prone and legislation stipulated that new

buildings 15 metres or higher must be built to withstand a

7.0-magnitude quake. Yet the law is not retroactive, and countless

older high buildings constructed before that year still dot the land

without any consideration of seismic loading.

Thailand was shocked to see a home-grown earthquake scar the land in

the North. It arrived out of the blue, and was considered a wake-up

call for action. Now a second alarm bell needs sounding - this time

alerting a shaken country to the distant underground menace facing

all-important Bangkok, home to canyons of skyscrapers situated on soft,

shaky ground.

(Shawn Kelly is senior media specialist at the Asian Institute of

Technology, Pathum Thani.)

The original article can be read at this link:

http://www.nationmultimedia.com/opinion/Bangkoks-tall-buildings-sitting-on-soft-shaky-grou-30234105.html